My Friends,

This post is not to confuse, its meant to join some dots we have covered in a few different places. My pages contain information to show any interested builder how to achieve a COP < 2.0, but typically, this is the limit, for what I have shared to date. Why is this the limit, because the Energy Stored in an Inductor is: $E = \frac{1}{2} L I^2$. This means, instead of one half, we get one whole, which we will go into later. That is, unless you have done the extra study and work to gain a little more info. Ruslan also told you a similar thing, that without the Nano Second Impulse, which is directly linked to the: 2.8GHz EPR Resonance Frequency, the Above Unity Gains is approximately: COP < 2.0.

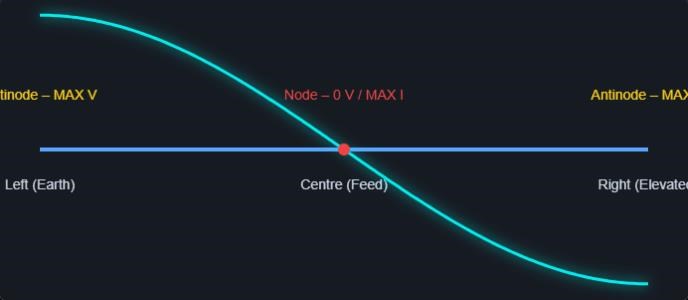

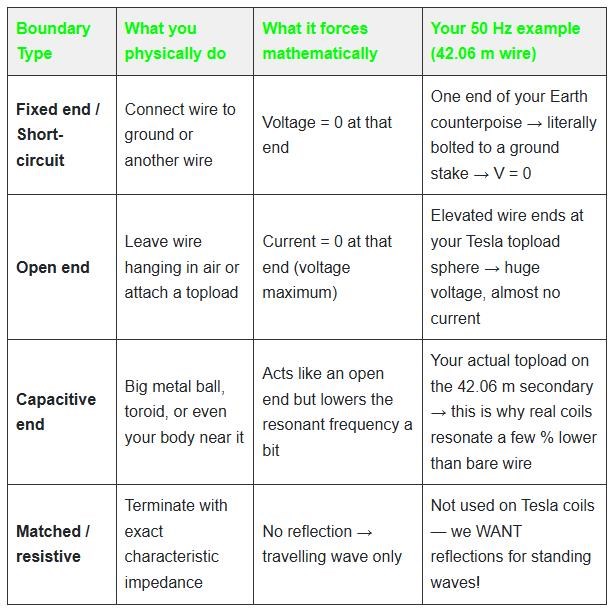

Maximum Voltage

The maximum Voltage obtainable on a Wire is when the Wire is in Resonance, a Wave Guide, and the Wavelength is equal to One Half the Wavelength of the Wire. This means, when one end of the Wire is Peak Positive Voltage, while at the same time, the other end of the Wire is Peak Negative Voltage.

Where:

- The Straight line is your Wire, the Length is the Length of λ/2 which is a Half Wavelength.

- The Teal, Half Sinusoidal Waveform, is the Resonant Waveform at λ/2.

- The Amplitude is shown, at VMax and VMin on the Wire Terminals, each end is:

one end of the Wire is Peak Positive Voltage, while at the same time, the other end of the Wire is Peak Negative Voltage.

At Resonance, the Wire has minimum Impedance!

An Example from History

Many years ago, we had a man show us some amazing things: Tariel Kapanadze:

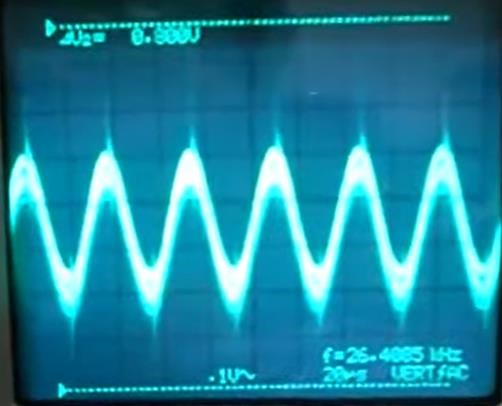

We have seen Input Waveforms like this:

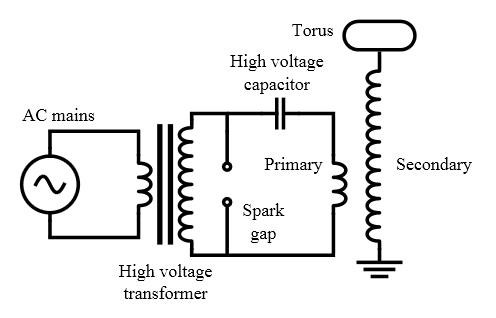

Which can be achieved using the Great Nikola Tesla's Spark Gap Circuit famous in his Tesla Coil:

You may remember a few posts like this:

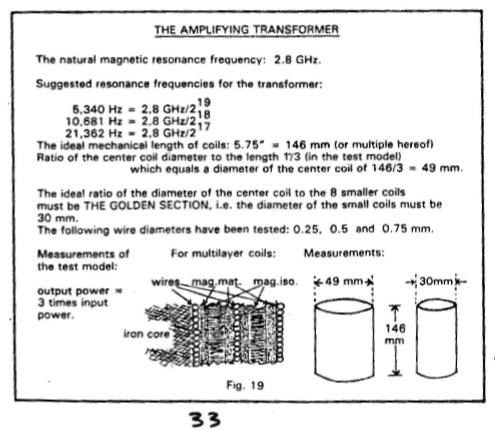

Floyd sweet has this to say about it:

Natural magnetic resonance freq = 2.80GHz the nuclear magnetic resonance of a free electron when charges in magnetic states are induced by magnetic field the changes in states causes a condition called electron paramagnetic resonance, or EPR. The EPR of a free electron is 2.80 H MC. Where H is in gauss.

Alfred Hubbard gave us this insight:

You may be also asking why the Nano Second Pulse, Impulse Pressure Wave, and the Spark Gap have featured in so many devices through out history? We need to think about these things! Floyd Sweet, in several papers, looked at "Wave Mechanics" ideas:

As the low level oscillatory frequency (modulating frequency) from the oscillators pass through zero reversing polarity during Δt. The quanta, being polarized, flip in synchronism with the modulating frequency, presenting a change in flux polarity varying with time determined by the period of the oscillator frequency. Stationary field and stationary stator coils are featured in the machine. Except for a possible low level 60 Hz hum, the alternator is noise-less. There are no bearings or moving parts.

Ref: Floyd Sweet - The Space-Quanta Modulated Mark 1 Static Alternator - Key Word: flip

Here I give you what I have learned over the years, and had a bit of help from AI to make sure its all correct to the best of my ability and the AI.

A Comprehensive Synthesis : The 2.8 GHz Quantum-Classical Resonance Bridge

This essay provides an exhaustive, multi-domain analysis of the 2.8 GHz frequency, focusing on the rigorous quantum requirements of Electron Paramagnetic Resonance ( EPR ) and the often-conflicting constraints imposed by classical electromagnetic theory, specifically concerning broadband sources and highly mismatched transmission lines. Additional context : 2.8 GHz falls within the S-band microwave range ( 2-4 GHz ), which is less common for EPR compared to X-band ( 9-10 GHz ) but is used in low-field EPR systems for studying larger samples, biological tissues, or in vivo applications where deeper penetration is beneficial due to lower absorption in water.

1. The Quantum Core : Rigidity of EPR and Spin Dynamics

The principle of EPR is built upon the Zeeman Effect, where a static magnetic field lifts the degeneracy of electron spin states. The process of successfully achieving resonance is far more complex than simply matching a frequency ; it involves precise field homogeneity, managing relaxation times, and considering hyperfine interactions in some cases. EPR is widely used in chemistry, biology, and materials science to study unpaired electrons in radicals, transition metals, and defects in solids.

1.1 The Larmor Condition and B₀ Precision

The fundamental resonance frequency ( ν ) is linearly proportional to the applied static magnetic field ( B₀ ), governed by the Larmor Equation :

\[ \nu = \frac{g \mu_B}{h} B_0 = \gamma_e B_0 \]

Using the fixed EPR frequency ν = 2.8 × 10⁹ Hz and the electron gyromagnetic ratio ( γₑ ≈ 2.8 GHz/T ), the magnetic field required is fixed : B₀ = 0.1 T ( or 1000 Gauss ). Any deviation from this field strength immediately shifts the necessary frequency away from 2.8 GHz. For a high-resolution EPR experiment, the homogeneity of B₀ across the sample must be maintained to better than 1 part in 10⁵. In practice, this is achieved using electromagnets with shim coils for field correction. At low fields like 0.1 T, superconducting magnets are not necessary ; but air-core or iron-core electromagnets are common.

1.2 Spin Relaxation Times ( T₁ and T₂ )

The efficiency and duration of the resonance process are governed by two critical time constants, measured in seconds :

- Spin-Lattice Relaxation ( T₁ ) : Governs how long it takes for the excited electrons ( in the higher energy state, mₛ = -1/2 ) to dump their excess energy back into the surrounding thermal environment ( the "lattice" ). This process is often an exponential decay : $$M_z(t) = M_{eq} - ( M_{eq} - M_z(0) ) e^{-t/T_1}$$ If T₁ is too short, the excitation energy immediately dissipates as heat, hindering the resonance. Typical T₁ values range from milliseconds to seconds in liquids but can be shorter in solids due to stronger lattice interactions.

- Spin-Spin Relaxation ( T₂ ) : Governs the loss of phase coherence ( transverse magnetization ). T₂ determines the linewidth ( Δν ) of the EPR signal, a critical parameter for defining the required frequency bandwidth of the B₁ source : $$\Delta\nu \propto \frac{1}{\pi T_2}$$ A longer T₂ means a sharper resonance line, requiring a more monochromatic ( pure sine wave ) 2. | 2.8 GHz source. Typical T₂ values in solids are in the microsecond to nanosecond range, leading to linewidths of kHz to MHz, demanding a very narrow bandwidth for the driving B₁ field. Inhomogeneous broadening from field variations can further affect T₂*.

Illustration 1 : The EPR Resonance and Linewidth Concept

Visualizing the energy splitting ( ΔE ) and the effect of relaxation on the required excitation frequency. ( Placeholder : In a real implementation, a JavaScript library like Chart.js could be used to draw the Zeeman splitting diagram and Lorentzian linewidth. )

2. Classical Source : Fourier Analysis and Power Decay

The spark gap is a classic example of a Pulsed Current Source. While simple to construct, its electrical output is fundamentally non-coherent broadband noise, the dynamics of which are defined by the Fourier Transform. Historically, spark gaps were used in early wireless telegraphy by pioneers like Marconi ; but their inefficiency at specific frequencies limits modern applications.

2.1 Spectral Power Density of a Current Pulse

The energy E delivered by the spark gap is defined by the capacitor : E = ½ C V². The Power Spectral Density ( PSD ) describes how this total energy is distributed across the frequency spectrum. For a simple rectangular current pulse of duration τ, the amplitude spectrum ( |F ( ν )| ) follows a sinc function :

\[ |F(\nu)| \propto \frac{\sin(\pi \nu \tau)}{\pi \nu \tau} \]

Beyond the corner frequency ( ≈ 1/τ ), the power of the harmonics decays rapidly, often following an inverse-square law ( ∝ 1/ν² or -20 dB/decade ). In reality, spark gap pulses are more exponential or damped sinusoidal, leading to a spectrum that rolls off as 1/f at lower frequencies and faster at higher ones.

To ensure measurable power exists at ν = 2.8 GHz, the pulse rise time ( τ ) must be exceptionally short, ideally in the picosecond range. If τ = 100 ps ( 0.1 ns ), the corner frequency is ≈ 3 GHz. This means 2.8 GHz is near the edge of the useful spectrum, where power begins to fall off dramatically. Modern equivalents include avalanche diodes or photoconductive switches for generating such short pulses.

2.2 The Challenge of Coherence

EPR requires a sustained, monochromatic B₁ field to drive the spin precession. A spark gap provides only a momentary, highly damped burst of energy. While this burst contains the 2.8 GHz harmonic, its instantaneous duration ( microseconds ) severely limits the efficiency of driving a continuous precession required for effective resonance absorption. For pulsed EPR techniques like electron spin echo, short pulses are useful ; but they still require high power and coherence within the pulse.

3. Classical Transmission : Extreme Impedance Mismatch ( L=40 m )

A 40 meter wire is fundamentally an inefficient radiator at microwave frequencies, defined by Transmission Line Theory. The efficiency of power transfer is governed by the characteristic impedance of the line ( Z₀ ) and the impedance of the load ( Z_L ). At 2.8 GHz, the wavelength is approximately 10.7 cm, making a 40 m wire equivalent to about 374 wavelengths, behaving like a traveling-wave antenna with poor efficiency for end-fire radiation.

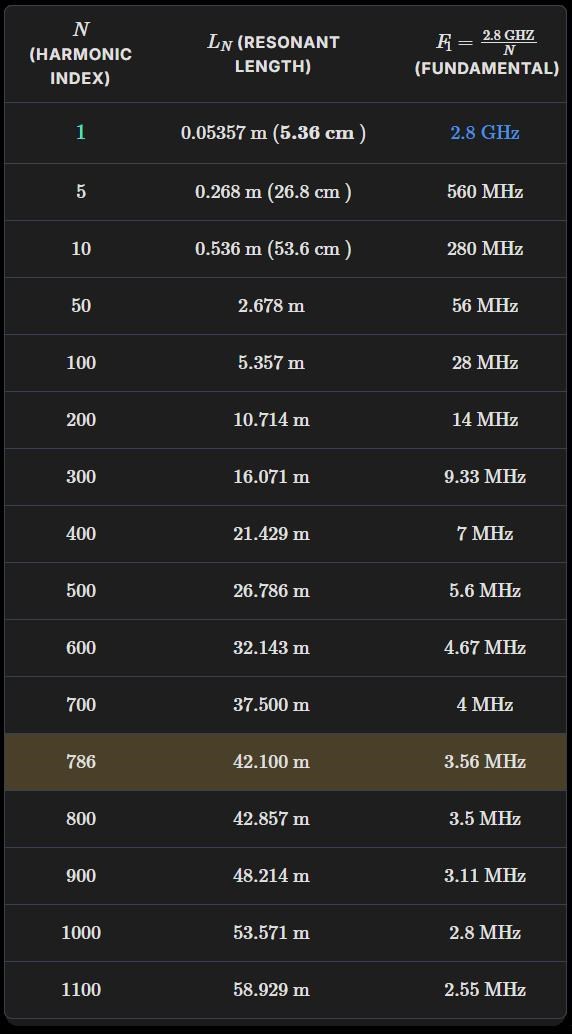

3.1 Fundamental vs. Harmonic Resonance

As calculated previously, the 2.8 GHz signal is approximately the 786th harmonic of the 40 meter wire's fundamental resonance ( f₁ ≈ 3.75 MHz for a half-wave dipole approximation ). The total radiative power ( P_rad ) is the integral of all components ; but the efficiency ( η ) for coupling the 2.8 GHz component ( ν_N ) is negligible :

\[ \eta \propto \frac{P_{\text{radiated at } \nu_N}}{P_{\text{input total}}} \]

Most power is radiated inefficiently or dissipated as heat ( P_dissipated ) in the wire, which increases with frequency due to the skin effect, where current is confined to the wire's surface, drastically increasing effective resistance ( R_AC ∝ √ν ). At 2.8 GHz, the skin depth for copper is about 1.2 μm, leading to high losses.

3.2 Reflection Coefficient and SWR

The Reflection Coefficient ( Γ ) quantifies the portion of power reflected back to the source due to impedance mismatch ( Γ = 0 for a perfect match ).

\[ \Gamma = \frac{Z_L - Z_0}{Z_L + Z_0} \]

For a long, highly non-resonant wire acting as an antenna at 2.8 GHz, the load impedance ( Z_L ) presented by the terminal and the radiation resistance will be drastically different from the line's characteristic impedance ( Z₀ ≈ 400-600 Ohms for a single wire ).

If, for example, the effective radiation impedance at 2.8 GHz is Z_L = 1000 + j1500 Ohms and Z₀ = 500 Ohms, the magnitude of the reflection coefficient is large, leading to an extremely high Standing Wave Ratio ( SWR ) :

\[ \text{SWR} = \frac{1 + |\Gamma|}{1 - |\Gamma|} \]

A high SWR means most of the energy is not transmitted ; but merely stands on the wire, generating heat. For an EPR experiment, this means the required B₁ field remains essentially zero at the target location. Mitigation could involve baluns or matching networks ; but at such high harmonics, it's impractical without specialized design.

Illustration 2 : Antenna Harmonic Disparity and Energy Distribution

Comparing the physical scale of the fundamental wave to the microscopic wavelength of the 2.8 GHz harmonic. ( Placeholder : A diagram showing wavelength scales and power distribution could be rendered here using JavaScript. )

Resonant Length Calculations for the 2.8 GHz Target Frequency

To determine the wire lengths ( L ) for which 2.8 GHz is a high-order resonance ( harmonic ), we rely on the fundamental relationship between frequency ( f ), wavelength ( λ ), and the speed of light ( c ).

Note on the 40 m example: The 40 meter length mentioned in real-world scenarios is slightly shorter than the theoretical 42.1 m (N=786) because of the antenna’s velocity factor (typically 0.95–0.98 for wire) and end-effects, which effectively reduce the required physical length for resonance.

4. The Coupling Solution : High-Q Filtering and Concentration

In professional magnetic resonance, the solution to the challenges of broadband noise and poor coupling is the use of a high-Q resonator, typically a microwave cavity. This component acts as a highly selective filter and an energy concentrator. Common types include rectangular or cylindrical TE/TM mode cavities, or loop-gap resonators for S-band EPR.

4.1 Power Gain via High-Q Cavity

The Quality Factor ( Q ) measures the efficiency of energy storage relative to energy loss per cycle :

\[ Q = 2\pi \frac{\text{Energy Stored}}{\text{Energy Lost per Cycle}} \]

A typical EPR cavity operating at 2.8 GHz ( an S-band frequency ) might have a Q value of Q ≈ 5,000. This high Q means the resonator can accumulate and sustain a massive internal power density from a weak external source. The voltage gain ( Aᵥ ) at the resonant frequency ( ν₀ ) is proportional to Q :

\[ A_v(\nu_0) \approx Q \]

If the spark gap delivers only 1 mW of power at 2.8 GHz, a cavity with Q=5000 could theoretically achieve an internal standing wave power equivalent to 5 Watts if efficiently coupled. This is the only way to generate a sufficient B₁ field for resonance. In practice, coupling is adjusted via iris or loop to match critical coupling for maximum power transfer.

4.2 Bandwidth Filtering Example

For a 2.8 GHz cavity with Q=5000, the bandwidth ( Δν ) that passes energy efficiently is extremely narrow :

\[ \Delta\nu = \frac{\nu_0}{Q} = \frac{2.8 \text{ GHz}}{5000} = 0.56 \text{ MHz} \]

This narrow band isolates the tiny 2.8 GHz harmonic from the overwhelming power present at lower frequencies ( e.g. , 3.75 MHz ) from the spark gap/long wire system. Higher Q values ( up to 10,000-50,000 in superconducting cavities ) can be achieved ; but may require cryogenic cooling.

Illustration 3 : Power Spectral Density and Q-Factor Filtering

Demonstrating how a high-Q filter isolates a weak harmonic from the broadband noise ( log scale ). ( Placeholder : A spectral plot with sinc function and Lorentzian filter could be drawn here. )

Final Synthesis and Conclusion

The analysis confirms that the successful exploitation of the 2.8 GHz frequency for EPR is a monumental challenge that bridges vastly different scales and physical laws. The long wire serves as an extremely inefficient, lossy, high-harmonic radiator for the source ; while the quantum mechanics of the spin system requires a monochromatic, high-power, high-coherence B₁ field delivered into a static field of exactly 1000 Gauss.

In summary, achieving this specific quantum mechanical interaction using simple, classical broadband components requires either a massive power input to brute-force the inefficiency, or the introduction of a highly precise, high-Q microwave component to selectively filter and amplify the necessary 2.8 GHz harmonic. Modern EPR systems often use solid-state amplifiers or klystrons for coherent sources ; but historical or DIY approaches might explore filtered spark gaps in educational contexts, though with limited sensitivity.

.jpg?width=690&upscale=false)